Grant and Mary Featherston:

Design for Life

By Denise Whitehouse

This short biography of the designers Grant and Mary Featherston was first published in Mid-Century Modern: Australian Furniture Design, Curator Kirsty Grant, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 2014. The illustrations in this version are different with an emphasis on drawings.

Born in 1922 Grant Featherston had a quintessentially Australian childhood growing up in the regional centre of Geelong. The Featherston family lived in a weatherboard house with the front garden devoted to floral display and the backyard to vegetable gardens, work sheds and children. His parents, Stanley and Eva, fostered family pride in things well made and it was his father, a pharmacist by profession, who helped him design his first piece of furniture, a folding drawing desk. It was this country-town childhood of tinkering in backyard sheds combined with beach and country holidays that fostered his passion for the environment and his fascination with science and technological progress.

The Geelong of Featherston’s childhood was not a parochial backwater. In the mid to late 1930s when he was beginning to think about his future, Geelong was embracing modernization and manufacturing. As an industrial port and centre for Victoria’s affluent Western District, Geelong had a dynamic blend of primary and secondary industries, in part stimulated by Ford, which supported a progressive technical education system dedicated to art, industry and manufacture. As Robin Boyd noted in Victoria Modern, Geelong was not only producing significant modernist architects but also significant modernist buildings including Laird and Buchan’s Pilkington Automotive Glass Factory (1936) which looked ‘more like a Gropius design than anything previously seen in Victoria.’ (1)

The excitement for modern industries was high when Featherson was in his final year at Geelong Technical School and his drawing abilities attracted the attention of the Melbourne glass manufacturer Oliver-Davey Co. Moving to Melbourne in 1938 he spent a year with Oliver-Davey before joining the lighting firm Newton and Gray Pty Ltd where he had his first introduction to plastics. These were formative years that shaped Featherston’s interest in the plasticity of materials and form together with his understanding of the factory floor and the processes of industrial production. They also introduced him to Melbourne’s furniture manufacturing industry in the Emerson Bros factory that was next door to Newton and Gray in Wells Street, South Melbourne.

With the advent of war Featherston enlisted in August 1941 confidently naming his employment as ‘industrial designer’ in a reflection of the growth of design for manufacture as evidenced in the formation of the Design and Industry Association of Australia (1939) and the Australian government’s wartime linking of modernist design with postwar reconstruction planning, especially housing and social infrastructure. For Featherston the war was a life-shaping trauma that fostered his deep belief that the quality of the human experience should be the central concern of all design. Like many he was drawn to Moholy-Nagy and Gropius’ ideal of ‘design for life’ which proposed that while design involved ‘the integration of technological, psychological, social and economic requirements, biological needs,’ it also involved the organization of emotional, social and cultural patterns for ‘working together as civilized human beings.’ (2)

With the return to civilian life Featherston married Claire Skinner in July 1945 and with entrepreneurial flair and an urgent need for income they set about making their own opportunities beginning with the design and manufacture of glass jewellery for the couture market. The success of this venture financed the development of Featherston’s first furniture range which he launched in November 1947, with the help of Robin Boyd in the Small Homes Section of The Age. Contextualising the chairs within ‘enlightened’ world developments, Boyd explained their originality as an introduction to good design: the economic use of plywood for machine production; ingenuous combination of materials-webbing and rubber cord- moulded to functionally fit the figure in a relaxed position; honest line and simple sculptural beauty. With their functional emphasis on relaxation, the chairs, Boyd explained, were a response to the changing social patterns that were informing the design of the modern small home. (3)

Featherston’s success was partly due his astute use of the media to promote his furniture within a wider debate about the need for good, that is, -professional-design. He began this practice in 1948 when, while working with his mentor Richard Haughton James and others to establish the Society of Designers for Industry (1949). Writing in Australian Home Beautiful, he outlined the difference between good and bad furniture design and explained how his Relaxation chair was leading a shift from craft to design for the machine. It was not designed for glamour and historical appeal, but for function and efficient production. Its function was to support the seated or reclining body naturally and bring a physical and psychological ease to contemporary life. This, he pronounced, was ‘modern design- the rational beauty of things made for use.’ (4)

In 1949 the Red Cross Modern Home Exhibition saw Featherston and his furniture take a central role in Melbourne’s modernists campaign for design-led manufacturing reform. A joint venture of SDI and the University of Mlebourne’s architecture department, and organized by James around the theme, ‘Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow’, the show was a manifesto for social change. The highlight was Boyd’s ‘House of Tomorrow’, which furnished throughout by Featherston, offered a tangible model of what contemporary living could be. While the exhibition established Featherston’s potential as a designer-manufacturer, it also started his career as a cultural spokesperson: he joined James and Boyd in encouraging the public, through talks and media interviews, to embrace modernist design that, while unfamiliar, was well suited to the Australian climate and way of life.

The Relaxation series offered the consumer a choice of models, colours and coverings 1948-1951.

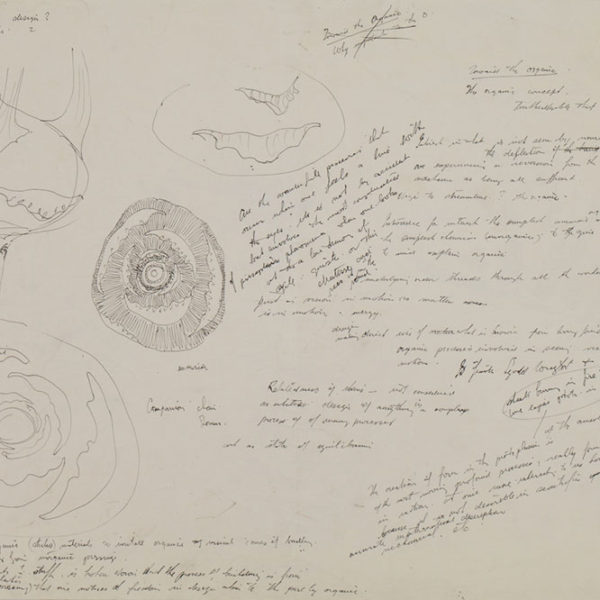

Featherston’s House of Tomorrow’s furniture won ‘almost universal approval’ and the demand for the Relaxation range and private commissions enabled him to establish a small factory in Collingwood where he set about educating himself in the art and practicalities of furniture manufacture. The archives indicate a period of intense experimentation with materials and form as Featherston studied the mechanics of things- upholstery, componentization, structure and detailing-while developing his design toolbox- sketching, technical drawings, promotional graphics and photography-, all the time reading about art, aesthetics and design. Much of this early work was clunky but there were the breakthrough pieces like the skeletal Cord chair, 1950, with its references to Henry Moore and contemporary art’s pursuit of a humanist aesthetic grounded in living form. (5)

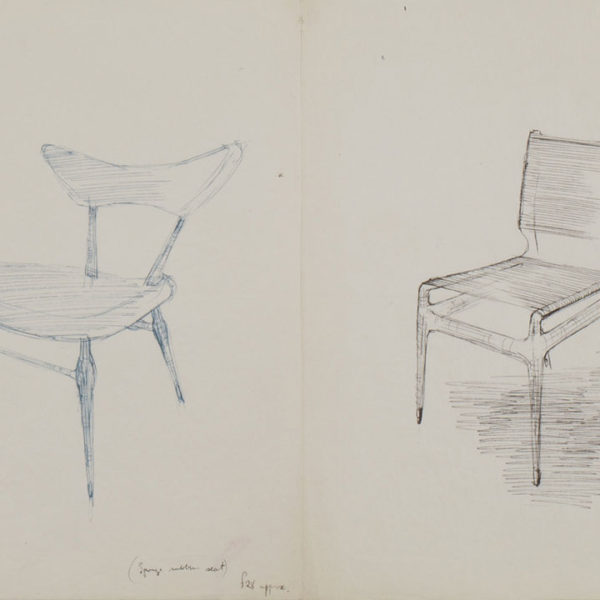

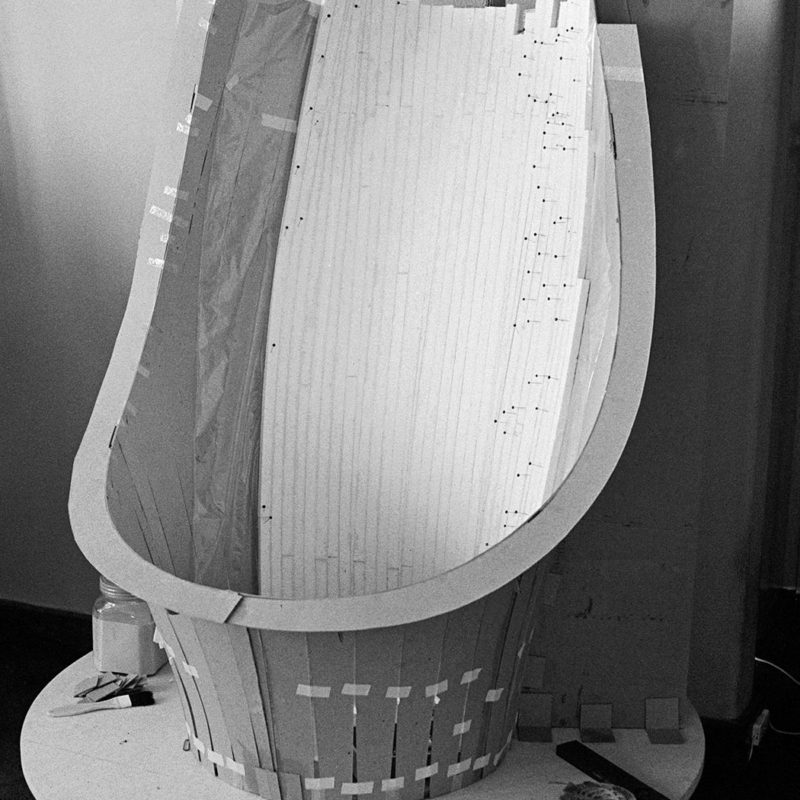

Featherston would develop the Cord chair’s language further throughout the 1950s for conservative commissions, especially desks and buffets, but its production was labor and material intensive and ‘arty-crafty’. His ambition was a chair that made minimal use of materials and could be mass-produced. Taking inspiration from the Eameses’ play with the plasticity of materials, he made his breakthrough sometime in 1950 when, playing with a tram ticket, he discovered of a method for bending two sheets of plywood to shape the simple compound curve shell that he would develop into the Contour chair which he patented in May 1951.

Although the invention of the Contour chair was announced by Boyd in the Age’s Small Homes Section in May 1951, it was not until Featherston’s Stanley Coe Gallery exhibition in June 1952, that the ingenuity of his ‘first attempt at mass production’ became apparent. (6) As the press reported, the form-fitting chair, with its thin upholstery, simple undercarriage and tapered legs, was unrivalled in its graceful elegance. More significantly, it was an entirely new approach to furniture manufacture. As a designed system the chair offered consumers the choice of different types of seating according to function (rocking, dining, relaxation, card-playing, business) each of which came in different heights and colours according to need. (7) Further, as the exhibition at the Hotel Federal in July 1953, and subsequent exhibitions, illustrated the system lent itself to the development of seating families, which, combined with Featherston tables, buffets, desks and Modular Storage Units (1955) formed the core of a cohesive aesthetic for the contemporary interior. The release of new models, each with distinctive personalities and technical innovations (Curl Up ,1953, Television, 1953, Eleanor, 1954, Cone, 1955) injected the Contour chair with an aura of the new and controversially modern. Featuring prominently in the architectural, trade and popular media, not only in articles on the contemporary home and interior design but also in retail advertising of domestic products, it became a touchstone of Australia’s growing cultural sophistication.

With demand high, Featherston licensed out the Contour chair’s manufacture, beginning with Emerson Bros in late 1952, to concentrate on building Featherston Contemporary Furniture into a design brand along the lines of Herman Miller and the Eameses. Drawing inspiration from their promotional campaigns, he worked to develop a consistent language of innovation and excellence across his practice including exhibitions, product photography, graphics, promotional material, articles and press releases, while ensuring the Contour chair’s placement within progressive -especially architectural contexts. At the same time he began to develop new furniture types to meet the demand coming from the rapidly expanding private and public sectors and clients as diverse as University of Melbourne, Chevron Hotel, ANZ Bank, ICIANZ, Qantas, Camberwell City Library and H. J. Heinze.

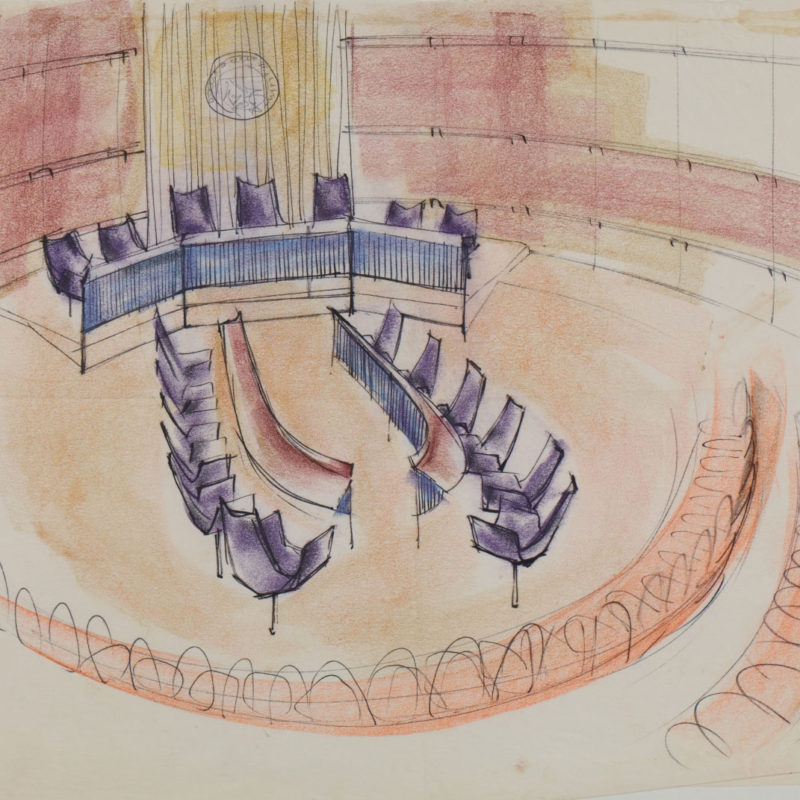

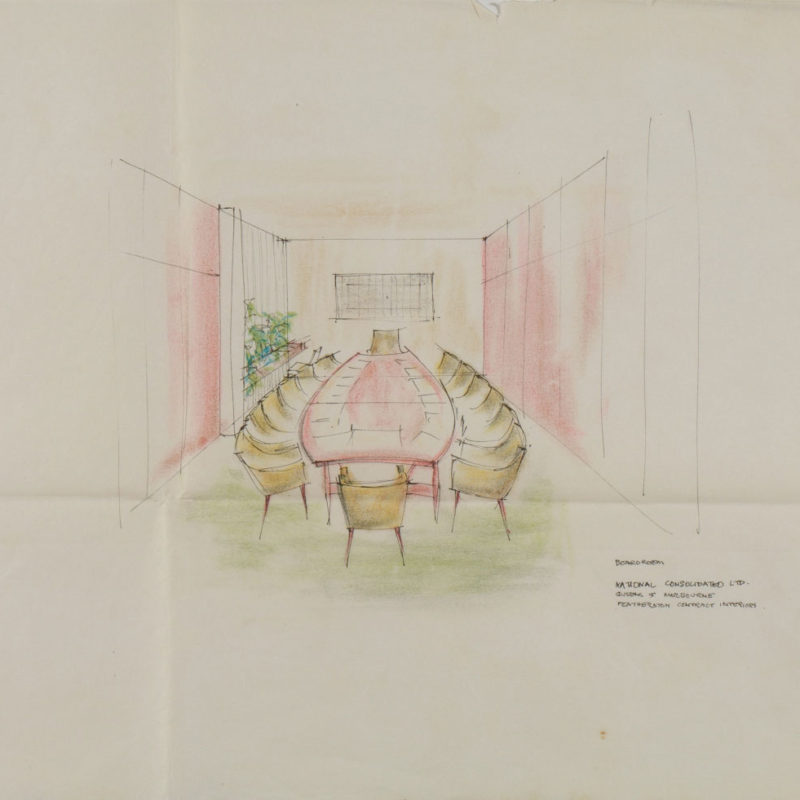

In August 1956 Featherston, in another entrepreneurial move, opened arguably Australia’s first modern furniture showroom, Featherston Contract Furniture, in Davidsons Place, off La Trobe Street. With its interior designed to showcase his expertise, Featherston Contract Interiors, as it became in 1958, offered an integrated service to architects and their clients that included the supply and development of furniture together with total interior design needs. Like Knoll Design, FCI worked with leading architects to define the practice of contract design, shaping the scope and aesthetics of the furniture and interiors to express the corporatizing values of modern business. (8) With few models to follow, Featherston used commissions involving total fit-outs, such as Australian National Travel Association (1959), Royal College of Pharmacy (1959-60), and National Consolidated Industries (1960) to meticulously research users needs and design furniture to suit. In the process he developed a functionalist system thinking approach that, applicable to everything from boardroom tables to lighting and storage systems, was exemplified by his Modular Office Units (1956-58) that shaped the hierarchical language of the modern office, from typing pools to executive suites. He also developed a language of innovation for the managerial level and prestigious projects such as Oakley & Parkes’ Brighton Municipal Council Offices (1959-61) where his Floating (Series 102) chair and radical modernization of the Council chambers placed the architects and their clients at the forefront of change.

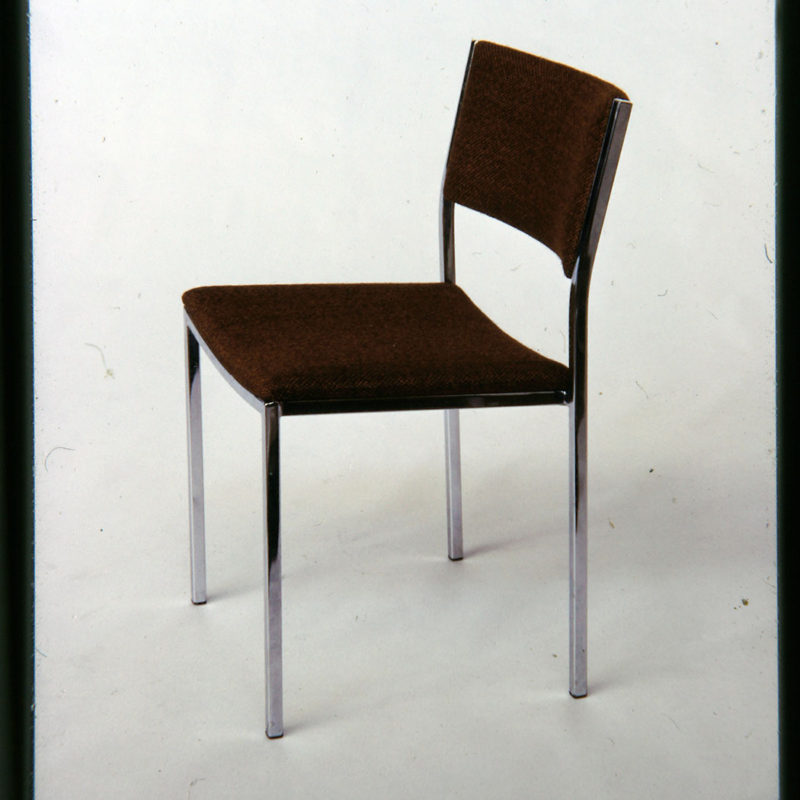

In 1961-2 the ownership of FCI passed to Aristoc Industries, with whom Featherston had been collaborating in developing new types of steel framed furniture, beginning with the Mitzi range in 1957, quickly followed by Arabesque, 1958, Pagodaline, 1958, and Scape,1960. A small manufacturer Aristoc valued the patented product and was prepared to invest in research and development, especially when Mitzi, a stylish stacking chair that appealed to both the domestic and contract markets, gave them immediate market success. Working closely with the management and factory teams, 1957-1969, Featherston developed a vast range of general-purpose furniture and in the process produced two of the highest selling Australian design chairs in Mitzi and Delma 1963 and over 40, Industrial Design Council of Australian (IDCA), Good Design Award winners. He also helped shape Aristoc into a Herman Miller style business whose design leadership was evident not only in its cutting edge corporate identity and advertising but also its management’s involvement with the IDCA and Industrial Design Institute of Australia.

A charismatic figure, who inspired and mentored those around him, Featherston had incredible creative energy and drive. While working for Aristoc ,he ran an independent consultancy, which became a partnership in 1965 after he married, the interior designer, Mary Currey (born 1943). In January 1966 the couple began work on their first joint project, the Expo ’67 Talking chair, 1966, for the Montreal World Expo. On its completion in August 1966, they immediately began the fit-out of Roy Grounds’s National Gallery of Victoria (1966-68). Fresh out of RMIT, Mary worked as an assistant on these projects, both of which were formative for the consultancy in terms of research and development and in the manner in which they placed the individual at the centre of a purposefully designed cultural experience. While the polystyrene Expo ’67 Talking chair, with its implanted sound system, was a research exercise in advanced materials and technologies it was also an exercise in physically and psychologically shaping the Expo visitor’s experience of Australia. (9) Similarly, while the NGV fit-out involved systematic consultation to identify the detail of users needs, it also involved the development of a modular furniture system that shaped the gallery visitor’s spatial and sensory engagement with the collection.

The Featherstons found relief from the politics of the NGV project by commissioning Robin Boyd to design a shed-like house (1967-69) with an enclosed garden, in an expression of their belief that design, like life, should be embedded in the nature. Boyd’s design was architecturally radical and the Featherstons embraced its potential as an integrated work home environment in which to base their further experiments with plastics technologies beginning with the Stem dining setting,1969. (10) While their interest in plastics was a response to European developments it was also inspired by their concern with environmental issues and waste. The challenge being to simplify the chair to a single component part and minimize the use of materials. There was also the aesthetic challenge of creating rigorously simple, organic forms that would bring playful Pop sophistication to domestic furniture.

But Australian manufacturing was notoriously conservative and as Stem hit the market, Aristoc which supported its research and development, was reshaped into Furniture Makers of Australia. With their manufacturing now focused on adapting overseas patents, their collaboration with the Featherstons ceased. A period of difficulty followed as the Featherstons sought sympathetic manufacturing partners in a marketplace flooded with imports and copies, including copies of Featherston furniture. Despite the difficulties they continued pushing boundaries and produced some of the most aesthetically and technically sophisticated furniture of the 1970s; the Poli lounge suite, 1971, Numero lounge suite IV, Numero lounge suite VI, 1973-4, and the Obo chair 1974, the last significant chair developed by Featherstons.

The 1970s was a period of activism for the Featherstons as they responded to world concerns about cultural change, the environment and mass consumerism. While Grant continued his work with the IDCA and IDIA lecturing widely and promoting socially responsible design, Mary became involved with the research and design of learning environments that placed the child at the centre of the experience. The important design issue as Mary defined was the lack of research into the needs of children within educational environments. With Grant’s support she developed the Children’s Museum at the Museum of Victoria (1984-1988), breaking conventions by designing exhibitions according to children needs and curiosity that actively encouraged children and families to physically touch and explore displays. The Children’s Museum led to exhibitions and curatorial commissions culminating with the Reggio Emilia Foundation’s ‘The Hundred Languages of Children’ (1994-2009). This travelling exhibition was pivotal in stimulating interest in alternative pedagogical practices amongst school communities and a demand for child-centred models of school design. Since the 1990 decades, Mary has been working collaboratively with school communities to develop interior and furniture systems which, sometimes controversial, have provided influential models for educationalists, researchers and architects involved in the current school design revolution.

As committed modernists the Featherstons, like Robin Boyd, believed that design, like art and architecture, should intellectually engage with ideas about what it means to be Australian. Their achievement of this goal, was celebrated in a major retrospective of Featherston chairs at the National Gallery of Victoria in 1988. (11) By presenting their furniture as aesthetic masterpieces, the exhibition highlighted their successful integration of excellence and beauty into the mass production of furniture for everyday living, and thereby, their significance within our cultural history. When Grant Featherston died in 1995 the Featherston chair, most especially the Contour chair, was well established as a design icon for young Australians searching for a design heritage that includes beauty and sophistication. Having captivated a new generation’s imagination the Featherston chair and its designers continue to gain popularity at an extraordinary rate both here and overseas.

Reference List

Unless otherwise cited the information in this essay is drawn from the Featherston archives, Ivanhoe Victoria, and interviews with Bruce Anderson, Neil Clerehan, Mary Featherston, Helen French, Ian Howard, Lindsay Jenkins, Kevin Knight, Eugene and Kevin McDonald, Diane Masters, Phyllis Murphy, Barry Oliver, Jan Pallaoro, Chris Palmer, Elizabeth Pilven, Winsome Plumb, Peggy Stone and Douglas Tomkin

- Robin Boyd, Victorian Modern, Architectural Students Society of the Royal Victorian Institute of Architecture, Melbourne, 1947, p.20.

- Featherston kept of copy of this passage by Moholy-Nagy pinned in his design studio, often referring to it in lectures and interviews. Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, Vision in Motion, Paul Theobald, Chicago, 1947, p. 42.

- Robin Boyd, ‘New Furniture’, Small Homes Section’, The Age, 26 November 1947.

- Grant Featherston, ‘Sitting Pretty’, Australian Home Beautiful, April 1948.

- While the exact date of the Cord chair is uncertain, mention of it appears on two occasions in the press in 1950: John Drake, ‘Your chairs can be made to fit you!’, The Argus Weekend Magazine, The Argus, 1 July 1950, pp.2-3, and ‘Experiments in design’, Weekend Arts Review, The Argus, December 1950.

- Robin Boyd, ‘Chair News’, Small Homes Section, The Age, May 1952.

- Joan Leyser, ‘Newest Australian Chair’, Australian Home Beautiful, May 1952.

- Bobbye Tigerman, ‘ “I am not a decorator”: Florence Knoll, The Knoll Planning Unit and the making of the modern office’, Journal of Design History, vol. 20, no. 1, pp. 61-74.

- Denise Whitehouse, ‘Speaking for Australia: The Talking Chair’: Ann Stephen, Philip Goad & Andrew McNamara, Modern Times: The Untold Story of Modernism in Australia‘, Miegunyah Press, Melbourne, 2008. Also Denise Whitehouse, ‘Encountering Art in the People’s Gallery: Grant and Mary Featherston and the Interior Furnishing and Fit-put of the National Gallery of Victoria,’ Art Journal of the National Gallery of Victoria, 54, 2014, pp. 9-23.

- ‘Designers at work: Grant and Mary Featherston’, Design Australia, no.14, June/July 1972, pp. 30-3.

- Featherston Chairs, 30 March-7 August 1988, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 1988, curated by Terence Lane.