A Matter of Influence:

The Swiss School and the Growth of the Graphic Design Profession in Australia

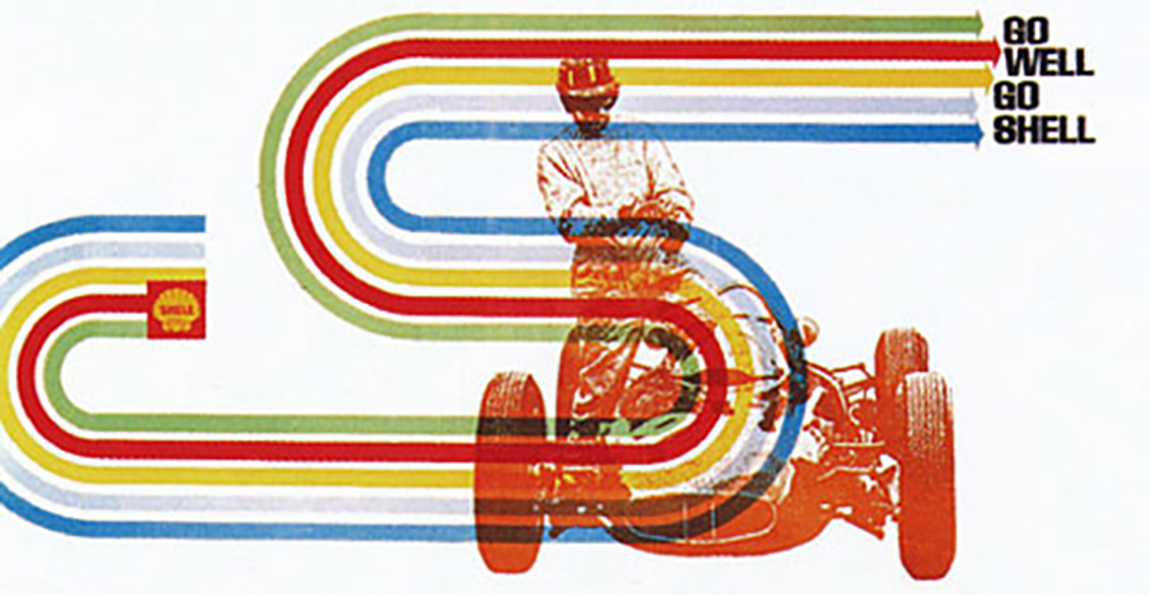

Frank Eidlitz, 1964, Posters for Shell

By Denise Whitehouse

The history of Australian graphic design has been told as a series of incoming influences. (1) Every other Australian born designer of the Post-World War II period tells the anecdotal story of their first revelationary encounter with “Design”. For some, this encounter involved seminal books such as Gyorgy Kepes’, The Language of Vision and Josef Müller-Brockman’s, The Graphic Artist and his Design Problems, while for others it involved journals Gebrauchgrafik, Graphis, Typographica, Print, Fortune where, through the advances of mechanical reproduction, they could study the latest international developments and, taking inspiration, adapt them to the Australian market using a process of improvisation and often blatant copying. For aspiring designers, isolated in the Antipodes, these publications offered encounters with the innovators of modern design, and most importantly insights into design as a new discipline and profession, whose function was modern communication. (2)

Lacking opportunities for formal design education many, Dahl and Geoffrey Collings, Gordon Andrews, Brian Sadgrove and Arthur Leydin for example, ventured overseas to experience this world first hand. Thus, it was in America that Brian Sadgrove came to understand the intellectual and theoretical impact of the Bauhaus émigrés on international design, while Arthur Leydin, working for the legendary Will Burtin, was able to experience a calibre of professional work and clientele unavailable in Australia and witness the international response to the teachings of Müller-Brockman and Max Bill whose journal Neue Grafik was revolutionising the way design was theorised and practised. There are many variations on the story of how true Design arrives in Australia. Perhaps the most mythic of which is that of the arrival of the immigrant designer who, like Richard Haughton James (1940s), Harry Williamson (1950s) and Les Mason (1960s), brings with them authentic design experience and knowledge. Within the regional backwaters of Australia they become luminaries with the west coast American import, Les Mason, for example, being credited with breaking the dominance of conservative English ideas about ‘commercial art’ by promoting the idea and practice of ‘graphic design’.(3) Viewed collectively these stories reflect the psyche of a colonial settler nation which, geographically isolated from its cultural origins, looks compulsively outwards, ever eager to be up with the new. Ideas about design come from elsewhere, which is not surprising given that as a small, primary industry nation, Australia lacked the government and market will to develop a design industry. More positively, they speak of the openness to ideas that saw a new generation of designers embrace international modernism, and with it the Swiss School ideal, to advance graphic design as a new and much needed professional practice in the late 1950s and 1960s.

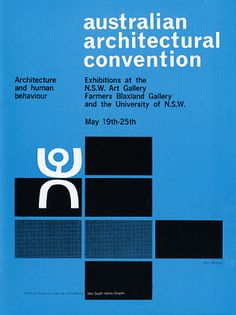

Harry Williamson, 1962, AACA Poster

The influence of the Swiss School of graphic design, as promoted by Armin Hofmann, Max Bill, Josef Müller-Brockman, Karl Gerstner and their contemporaries, arrived via circuitous routes; through individuals but mostly through publications the most influential of which was Neue Grafik,the design bible of the era. In contrast to Britain’s Penrose Annual or America’s Print, it was radically self-aware in its disciplined use of the grid for order, its treatment of typography (sans serif) as form and space, and its overall gestalt that, in unifying form and content (image and text), presented information objectively, without manipulation. Published with an English text, Neue Grafik provided Australians with a practical visual model and access to theoretical essays that, in outlining the principles of international typography and print design, defined graphic design as a discipline with its own philosophy and history, its own tools, practices, technologies and rules. This struck a deep cord in a country that, lacking a tradition of formal design education, was, as Haughton James explained, experiencing a real demand for educated designers who could not only fulfill the demands of the marketplace but also set standards and act as social and ethical problem solvers. (4)

Swiss School design with its rhetoric of internationalism became the fad of the day, paralleling the craze for Abstract Expressionism and Colour Field painting which, together with the corporate skyscrapers that were internationalising Australian cities, created considerable controversy. For many, including the art historian Bernard Smith, this wholesale embrace of internationalisation amounted to a failure of belief in Australia’s distinctive regional culture as evidenced in its booming literature, arts and theatre production. Most importantly, the cultural confidence that fuelled this tussle between the internationalists and the regionalists also fed an impassioned call for a new design intelligence to deal with the impact that the expansion of advertising, consumerism and the mass media was having on everyday life. As the architect Robin Boyd argued in his scathing critique of Australian aesthetics, The Australian Ugliness (1960), unbridled urban expansion was creating a world of visual squalor and chaos in which ideals of collective standards and order were being over ridden by economic interests. Attacking Australians for their love of the vulgar, Boyd argued the case for a national aesthetic grounded in the modernist ideal of design as a process of intelligent thought and problem solving dedicated to function, technology and aesthetics. He proposed that the people who held the solution to the environmental mess were designers because, committed to the higher order of ideas, they were able to create aesthetic order and standards while accommodating conflicting economic demands. (5)

Boyd was not alone in his concerns, which interestingly echoed those of Müller-Brockman who stated that ‘The visual racket of the consumer machine can be surpassed only by intelligent and creative design.’ (6) As Haughton James wrote in 1968, the expansion of the mass media and reproduction technologies was creating a plethora of new communication tasks and social expectations that reached far beyond the traditional practices of commercial and advertising art. (7) A glance at ACIAA annuals of the 1960s reveals that these new challenges included the ever expanding field of print, together with the new fields of television and animation, corporate, trademark and logo design, packaging and typography. As these annuals were intended to be illustrated there was a shift away from old notions of commercial art with its subservience to advertising to graphic design as a specialist service industry in its own right. (8)

For an increasing number of individuals interested in design as a distinctive and different practice from marketing and advertising, the Swiss School, with its model of objective and informative communication design, offered a way forward. For a young Garry Emery with his training in the print trade the teachings of Max Bill, Müller-Brockman and Gerstner offered an intellectual pathway out of the old world of lettering into the contemporary practice of typography. Through their theories of ‘constructive’, ‘integral’ and ‘concret’ design he discovered typography as a formal language of symbols and signs, a system of readability and legibility grounded in the mastery of creating a gestalt out of predefined parts. He also discovered the aesthetics of typography: letters as pure form shaped from the tension of negative and positive space. Finally, Emery found that, as a disciplined practice that matched the conceptual rigour of modern art and architecture, modern typography had the potential to bring functional and aesthetic order to our everyday environments. (9) Similarly, emerging designers like Brian Sadgrove, Max Robinson and Ken Cato faced with the demands of new corporate, commercial and institutional clients, found practical guidance in the Swiss School’s definition of design as a problem solving practice grounded in a scientific approach to visual organisation and a deep understanding of the conceptual nature of visual language. (10)

Left: Brian Sadgrove, 1970, Channel Nine logo; Right: Ken Cato, 1991, SBS logo

The Australian embrace of the Swiss School was not about stylistic fashion as their critics claimed. Rather, it involved the shaping of a defining discourse about standards and professional identity that linked them into the larger world of international Graphic Design and positioned them as practitioners in modern visual communication. It also informed educational reform and the development of tertiary Graphic Design courses, firstly at Swinburne College of Advanced Education and later Caulfield CAE, which drew on Swiss teaching models to the extent that Hofmann’s elementary formal and poster exercises were still in use in the early 1990s.

The poster, which the Swiss had made their own, took on renewed significance as the par excellence manifestation of the graphic designer’s creativity and skill in abstract, non-verbal communication. However, the use of the poster for formal and technological experimentation was not new to Australia whose pioneer modernists, Gert Sellheim, Dahl Collings, Gert Sellheim, Richard Beck and Douglas Annand, had used it to test the potential of abstraction, new typography and photomechanical reproduction to shape a progressive visual rhetoric for Australian tourism. What was new was the graphic design fraternity’s adoption of the poster as the benchmark of excellence around which it organised exhibitions, competitions and publications that promoted the principles and function their practice. Hofmann stated that a poster can reveal ‘a society’s state of mind.’ (11) For Australian designers, it became and still is a signifier of their professional discourse, a non-verbal statement of standards and ideals. While speaking of the influence of the Swiss School it spoke of the quest for an aesthetic order and design intelligence that could meet the challenges of modern communication.

- Caban, G 1983, A Fine Line: A History of Australian Commercial Art, Hale and Iremonger, Sydney; and http://www.agda.com.au/

- Caban, G 1983, A Fine Line: A History of Australian Commercial Art, Hale and Iremonger, Sydney.

- Interview, June 2005, Garry Emery, South Melbourne.

- James, R H 1968, ‘Communications’, in J Button (ed.), Look Here! Considering the Australian Environment, F W Cheshire, Melbourne. pp.103-7.

- Boyd, R 1960, The Australian Ugliness, F W Cheshire, Melbourne

- Müller, L ( ed.) c.1995, Josef Müller-Brockman Designer. A Pioneer of Swiss Graphic Design, Lars Müller Publishers, Baden, Switzerland, p.38.

- James, R H 1968, ‘Communications’, in J Button (ed.), Look Here! Considering the Australian Environment, F W Cheshire, Melbourne, pp. 99-107.

- Australian Commercial and Industrial Artists of Australia Association 1962/63 & 1963/64 Advertising Art and Design in Australian: ACIAA Annuals,. ACIAA, David and Burton Group, Melbourne.

- Interview, June 2005, Garry Emery, South Melbourne

- Interview, September 2005, Brian Sadgrove, Prahran, Melbourne.

- Hofmann A, c. 2003 Armin Hofmann, Museum fur Gestaltung Zurich, Lars Müller Publishers, Baden, Switzerland.