The Modern Home Exhibition:

The Society of Designers for Industry

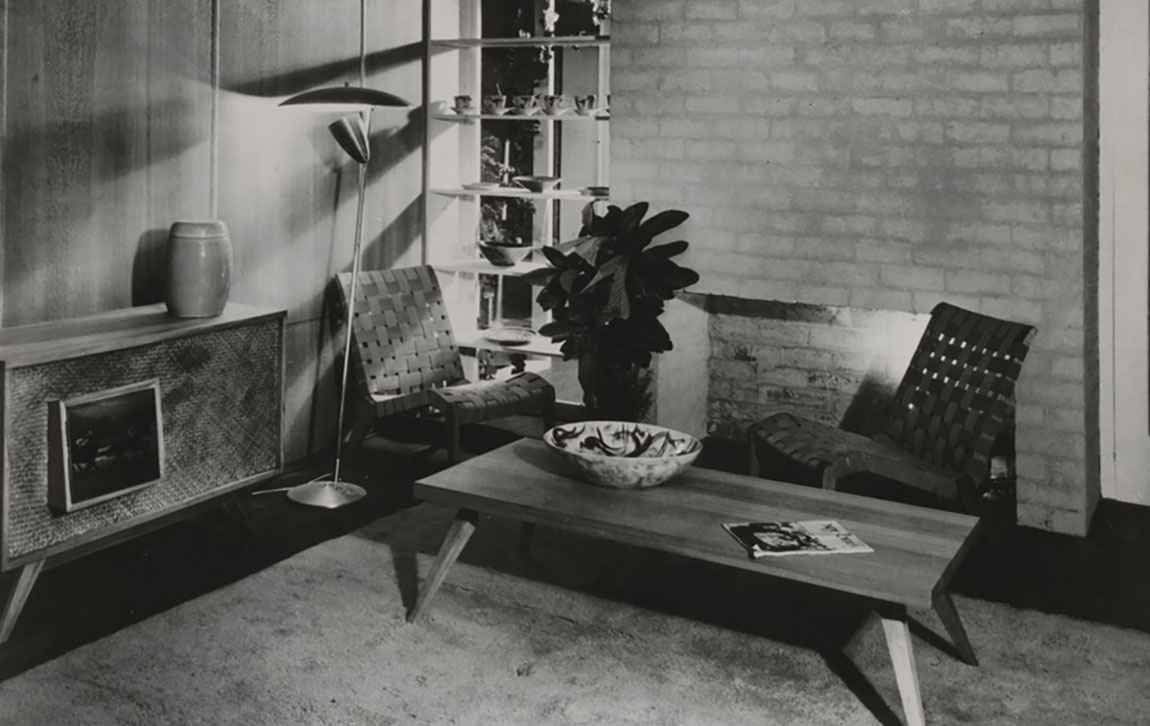

Modern Home Exhibition, House of Tomorrow designed by Robin Boyd with furniture designed by Grant Featherston. Photograph: Wolfgang Sievers, State Library of Victoria.

By Denise Whitehouse

The Modern Home Exhibition, Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow, opened in October 1949 in Melbourne’s Exhibition Buildings amid a blaze of publicity. Designed and orchestrated by Richard Haughton (Jimmy) James and his assistant Max Forbes, it showcased the ambitions of postwar modernists to drive social and manufacturing reform through the promotion of good design principles. James was influential postwar as he joined forces with the University of Melbourne’s newly appointed professors of Art History, Joseph Burke, and Architecture, Brian Lewis, to raise the standard of people’s engagement with design and culture. Full of optimistic belief in a design-led future, the Modern Home Exhibition provided a promotional platform for an emergent design profession and its organizational body, the Society of Designers for Industry. James was a driving force behind SDI, which formed in 1948 with the ambitious objective of defining Design as a profession akin in status to Medicine, Law and Architecture. Media savvy, James was SDI’s president and, as their chief publicist, he relentlessly lobbied government and industry about the importance of educated design practice: public education and promotion were central to SDI’s charter. Together with the University of Melbourne’s architecture department and members of SDI, he converted the Home Exhibition into a public relations opportunity that exploited the growing interest in design being fostered by the return to civilian life and market manufacturing. (1)

Drawing on the theorists of the British Art and Industry movement, especially of Herbert Read and John Gloag, James used the Home Exhibition to lead, what his contemporaries described as, ‘the first attempt at a continuous unified exhibition of one theme in Australian exhibition history’; the one theme being the principles of good, functional design, which stressed throughout, ‘created much enthusiasm and some cat calls’. (2) As he explained, this was no easy feat because, in contrast to overseas practice where extensive time was given to pre-fabrication and installation, the Modern Home exhibition, ‘covering the whole of the main floor-area and… the erection of a comfortably furnished house, had to be erect in one week’. (3) In an ingenious piece of design, he used ‘thousands of feet’ of steel tubing and simple colour to shape the displays into a cohesive, and somewhat didactic, narrative of modern progress-Living Yesterday, Living Today, Living Tomorrow. The hero of the narrative, was the House of Tomorrow that James persuaded Robin Boyd to build within the Exhibition Buildings, the aim of which, James told readers of The Age, was to show how contemporary ideas could be converted into the real houses for tomorrow, and what could ‘be achieved in the home by thought and planning’. (4) ‘Tomorrow’ had a particular resonance for visitors to the Home Exhibition who were eagerly waiting the lifting of wartime building restrictions.

The importance of James’ thematic approach was its presentation of design as a social and industrial practice with its own discourse, history, theory and principles, ‘the moral and social benefits’ of which were on display in Boyd’s model house. (5) Standing centre stage under the dome, Boyd’s House of Tomorrow was 13 square, two storey and fully furnished inside and out by new design professionals, including Grant Featherston. Constructed and fitted out in 10 days, with the assistance of Peter McIntyre and architecture students, it was an object of controversy as the public was, for the first time, able to view an architect-designed small home with an open floor plan and integrated interior design scheme that included electrical appliances, fabrics, lighting, floor and wall finishes and furniture; all products designed by SDI members. (6)

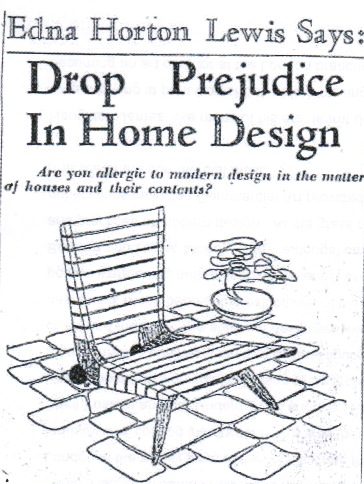

Warning the readers of the Melbourne Herald against their fear of the new, the design journalist Edna Horton Lewis explained that the ‘purpose of the house was to show visitors what architects and designers and manufacturers are doing to devise homes that fit modern pattern of living’. It was, she advised, important for the public to drop their prejudices and try to understand the economies of production and materials, and the health and living improvements being offered by Boyd’s house and Featherson’s furniture.

Sketches of Grant Featherston’s furniture, probably by him, featured in the press coverage including, ‘Edna Horton Lewis Says Drop Prejudices in Home Design’, Newcastle Morning Herald & Miner’s Advocate, October 28 1994.

The prototype furniture, Featherston designed for the House of Tomorrow, was an extension of his Relaxation chair range (1948) to include coffee tables, a prototype television cabinet, lightweight settee and an elegant, slim-line chaise longue that featured prominently on the patio. Made from simple webbing and plywood, the Relaxation chairs were ideally suited to the house, echoing the honesty of its structure, its austerity materials and its rigorous interrelationship of form and production methods. Strategically arranged with modern textiles by Frances Burke, lighting by Browns Evans and Co and art works by Arthur Boyd, the furniture injected life into the House of Tomorrow’s living spaces, adding colour and elegant form, while illustrating how appropriately designed furniture could bring spaciousness and a unifying, functional and aesthetic logic to the small home. (7)

In his role as editor of the SDI newsletter, Featherston mentioned he designed ‘special furniture’ for the Boyd house: some sketches for which were published in the exhibition publicity reports. (8) Simple and functional, it was, he told the press, intended to illustrate the new order of machine production that would, ‘provide furniture that was ‘mobile, flexible, honest and efficiently and easily produced. (9) While all the furniture was designed by Featherston only the Relaxation chairs were manufactured by him. The dining setting and bedroom furniture were manufactured by another member of SDI, Fred Lowen, and the padded lounge chairs were manufactured by LBC Wood Products. Significantly, there is no mention of Lowen’s involvement other than in the Exhibition’s catalogue that includes a Fler advertisement stating it manufactured the dining furniture. Lowen does not mention his involvement in his memoirs. But this was early in his career, when he was beginning to manufacture Fred Ward’s furniture designs for Myer, and had just enrolled in Melbourne Technical College’s new diploma in industrial design. And he was always carefully in his later years to place distance between himself and Featherston. (10)

Featherston’s furniture was a hit and, according to Boyd, it was auctioned off at the end of the exhibition. (11) The Exhibition helped launch Featherston’s career, stimulating public interest and, with this, private commissions that enabled him to experiment and develop the Contour Chair. Like James, who was his mentor, Featherston also featured on the radio and in the press as a spokesperson for SDI, using his furniture as a manifesto for change and to educate people about the practice of functionalist design as an international movement. He had set this good design dialogue in motion in 1948 when explaining to the press that his Relaxation series was inspired by the same questions that drove the Swedish designers, who were leading the world in the shift from craft to machine and creating furniture specifically for the needs of people. Rather than continuing to copy styles and production methods that dated back hundreds of years they were, like Marcel Breuer, rethinking the basics of furniture design and production and, with this, fundamental concepts such as relaxation and comfort. Indeed, it was Breuer’s scientific discovery that the body is most comfortable when fully reclined, that inspired the unconventional shapes of the Relaxation chairs that were formed to support the body, firmly but flexibly, in a range of semi-reclining positions.

Attacking the tradition of the three-piece lounge, Featherston argued that chairs needed to be designed according to their different functions within contemporary life. Accordingly, his Relaxation chairs were not designed according to glamour appeal, but according to what the body needs to be comfortably supported, when engaged in different activities, such as sitting in the living room reading and talking, or lounging in the sun outdoors. This, he concluded, was ‘modern design- the rational beauty of things made for use. The harmonious welding of material and function.’ (12)

The Modern Home Exhibition turned the spotlight, not only on the expertise of the new industrial designer, but also on the need for manufacturing reform, with Boyd’s house and Featherston’s furniture acting as models for what was possible. Dynamic and articulate, Featherston was promoted as the new, ideologically informed, expert whose furniture design was leading the way to mass production as well as a better way of living. His modernist furniture had no rivals within the context of exhibition and cut a stark contrast to the endless displays of reproduction Chippendale and Queen Anne furniture exhibited by mainstream manufacturers and retailers. It alone pointed to the possibility of new furniture types using machine production methods and this made it controversial. Edna Norton Lewis, told the readers of the tabloid press that his ‘comfortable modern chairs’, like the House of Tomorrow, were so new, so different, there was a danger that people would instinctively condemn them on sight. Recalling the stories of ‘visionary artists and designers’ struggles to have their ideas accepted, she explained that Featherston’s simple and light chairs were in fact practical because they addressed the need for flexible living spaces and that, easily moveable and devoid of ornament, they were intended to reduce the workload of the modern housewife. (13)

Featherston was just one of the SDI members who galvanised together to give radio talks, public lectures and press interviews and stimulate the controversy and interest that saw over 60,000 visitors over 2 weeks. (14) A key publicity strategy was SDI’s humorous good versus bad design scenario that was set up by students from Melbourne Technical College’s (RMIT) fledging industrial design diploma course. The good verses bad design theme was furthered fostered by the spectacle of a design jury and the colour coding of exhibits: green signified the past, white modern design and the future, while purple cards highlighted the jury’s choice of designs that would stand the test of time. While the good versus bad games reek of modernist didacticism, they were a very effective strategy for capturing the media’s attention. They also were effective in building design literacy and product awareness in the public, while playfully engaging them in the debate about design and cultural change with the emphasis being on practicality and commonsense. Significantly for a country where modern art and cultural sophistication were distrusted, the jury of three; one ’just a housewife’, another the American Vice-Consul and the third Professor Brian Lewis, used ‘commonsense’ as their benchmark which they illustrated by giving an award to a tiny biscuit cutter because it ‘was simple and cheap and worked well.’ (15)

The demand for Featherston’s work stimulated by the Home Exhibition prompted his decision to establish Featherston Contemporary Furniture and begin the serious manufacture and marketing of his furniture. Extending the Relaxation Range to include dining, living and bedroom furniture, he was able to capture the needs of an emerging educated middle class market, which the progressive furniture retailer, Bruce Anderson recalled, were excitedly embracing modern design as an ideological means to create a better and more honest world. (16) It also firmly established his presence as a media figure and his use of the modern chair as a discursive object that was reflective of changing social and cultural ideals.

As Featherston recalled, the Modern Home Exhibition captured the moment as no other exhibition had before or since. With trade stands promoting over seventy manufacturers, building suppliers, furnishing manufacturers, retailers and the influential, Woman’s Day and Australian Home Beautiful magazines, it offered a comprehensive picture of, what was potentially, the new field of professional design. It was essentially a gallery of modern Australian design in everyday things. In an ironic twist of history, it echoed the 1851 Great Exhibition experience of some 100 years earlier in that the bulk of the displays, when juxtaposed against the good design lessons of the House of Tomorrow, were found severely wanting, and this triggered widespread debate about production and aesthetic standards that still informs Australia’s design and cultural discourses. But like the Great Exhibition, it also captured a significant moment when economic and social change was forcing industry, largely against its will, to turn to designers in order to modernise it attitudes and practices.

- See the Richard Haughton James Design Archive, Powerhouse Museum, Sydney, for transcripts of his articles and lectures, and insights into his extensive use of design theory in his public promotion of professional design. Also, Richard Haughton James, ‘Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow’, transcript of 4 ABC radio talks, given over October and November 1949, explaining good design and the Modern Home Exhibition, James Archive, Powerhouse Museum. See also, Denise Whitehouse, ‘Richard Haughton James, Australia National Journal and the Designer for Industry’, DHARN.

- Grant Featherston, typed transcript for the Society of Designers for Industry Newsletter, c. November 1949, Featherston Archives, Ivanhoe, Melbourne.

- Richard Haughton James, ‘An Australian View of Exhibition Design’, transcript of lecture, given, as President, Society of Designers for Industry, to the Illuminating Engineering Society of Australia, November 1951, p. 2, James Archive, Powerhouse Museum. See also Ray Marginson, a memorial address, ‘Jimmy James; A Personal Memoir’, given at the Second Asia/Pacific Design Conference, Australia,1989, Mildura, August 26-29, pp25-26. Also Arthur Leydin, quoted in Marginson, p.25.

- James in ‘Tomorrow’s Home: Today’s Ideas, Exhibition Points to Better Living’, The Age, 19 October 1949.

- Featherston, Society of Designers for Industry Newsletter.

- ‘Tomorrow’s Home: Today’s Ideas’, The Age, 19 October 1949.

- Modern Home Exhibition, Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow, 20 October to 1 November, 1949, Souvenir Guide Book.

- Featherston, Society of Designers for Industry Newsletter; Boyd notes Featherston designed the furniture, in ‘House of Tomorrow is made for Today’, in ‘Tomorrow’s Home: Today’s Ideas’ The Age, 19 October 1949. See also Modern Home Exhibition, Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow.

- Grant Featherston quoted in ‘New Era of Furniture Design in Australia’, The Argus, 21 October 1949.

- Modern Home Exhibition, Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow. Also Fred Lowen, Dunera Boy, Furniture Design, Artist, Castlemaine, Victoria, Australia, Prendergast Publishings, c.2001, pp.104-5.

- Robin Boyd, ‘ Modern Home Exhibition Melbourne’, Architecture, vol. 38, no. 1 January 1950.

- Grant Featherston, ‘Sitting Pretty’, Australian Home Beautiful, April 1948.

- Edna Horton Lewis, Melbourne Herald, 19 October 1949.

- Featherston, Society of Designers for Industry Newsletter. Featherston reported ‘many talks and interviews with SDI members’ on all Melbourne radio stations, including one by himself on 3DB, as well as articles by Ron Rosenfeldt and Falconer Green.

- ‘New outlook in buildings plans; Emphasis on Design at Red Cross Homes Display; Showing follies of past and hopes of future’, The Argus, 21 October, 1949.

- Author interview with Bruce Anderson, Hawthorn, Melbourne, November 2005.